- excerpt from Ellen's journal

With a stack of recommendations and a two-page resume, she arrived in Washington a year ago last June. She was "36 and full of ideals," as she wrote in her journal, a sheaf of typed pages in a loose-leaf binder. She had been a real estate agent, an executive recruiter, a paralegal and lately an administrative assistant to the president of an architectural engineering firm in Bloomington, Minn.

She had enjoyed an upper-middle-class class childhood in Southern California, but struggled as a teen-ager through her parents' divorce and, later, two bad marriages of her own - the first a shotgun wedding at age 18, to a North Carolina country boy; the second, a brief, explosive marriage to a San Francisco man.

Fleeing her second marriage for Minnesota, where her mother was living, she was overtaken on the highway by a religious epiphany. She had weathered alcoholism, the painful separation from a daughter and son by her first marriage and a nagging sense of purposelessness. She had subordinated her identity to that of her parents and husbands. Now, at the wheel of her red Toyota, she decided in a flash to name herself Benjamin, "after one of the wandering tribes of Israel."

Three years later, in December 1982, she had another flash. Watching television in a farmhouse on the St. Croix River, she saw a news report of a man threatening to blow up the Washington Monument unless the world recognized the horror of nuclear holocaust. Norman Mayer was bluffing about the explosives, it turned out, but he was killed in a shower of police bullets.

"I remember sitting on the edge of the couch with tears running down my face, thinking, 'You crazy wonderful fool, there's no way you're going to walk away from this,'" she says.

"And I also recall seeing a man climbing the hill and going to talk to him. And I thought, 'My God, what a brave soul.' ... I decided I should be in Washington. It was a place where I felt I could have an impact."

Unbeknownst to her, this was her first glimpse of Thomas.

Six months after Mayer's death, she arrived in Washington and found work — first at a local marketing company, then at the National Wildlife Federation, an environmental lobbying group. She rented an apartment in a fashionable part of Capitol Hill and invited her 18-year-old daughter, who had been staying with her father and brother in North Carolina, to live with her and a woman friend. The three shared what Ellen now calls "a very comfortable bourgeois existence. I even had a wok."

She went to parties, dated — she and her daughter compared notes on boyfriends — attended poetry readings, indulged her fondness for good food and became increasingly dissatisfied.

"In this town," she discovered, "everybody says, 'What do you do? Who do you work for? Where did you go to school? What's your family? How much money do you make? What kind of car do you drive?' Ugh. It's an encapsulization of what's wrong with America . . . There were all kinds of fancy titles for what I was, but I was basically a high-class secretary. And all my life, I've wanted to make my living as a writer."

Her own experiences would seem to have presented a wealth of raw material — according to family lore, Mary Pickford once offered to make her a child star — but Ellen looked to the streets for inspiration. After work, she wandered through the downtown area interviewing winos and derelicts, gathering grist for "The Grate People," a play she planned to write about the homeless.

On one such expedition in Lafayette Square, she happened across Thomas. He was tending his antinuclear signs and preaching "Norman [Mayer]'s 10 Laws of Reality." "In a world of competing notions of reality," reads Norman's Fifth Law, "wise men must determine survival necessities on a priority schedule." Hours before Mayer's death, Thomas had become the last person to speak with him by crossing the police barrier at the base of the Washington Monument. "Get the hell out of here," he says Mayer advised.

Ellen snapped Thomas' picture and they talked. It was March 19, 1984, as she noted in her journal. "His hazel eyes were stern," she wrote. "His thick beard (threaded with single white hairs) bristled." That night the subject was Armageddon. But soon she was dropping by his vigil every day, and they talked of other things. Her journal includes their love letters.

Ellen: "[Early April] Monday night 9:36 p.m. ... my mind churning. Thomas, how bizarre the way this whole situation seems to be progressing. I came into the street like a bulldozer, may rape the garden you've tenderly cultivated and leave you devastated and alone. I may do that. I don't believe so . . ."

Thomas: "i believe in what you can be. i don't believe in what you are. i believe you can be a prophetess . . ."

Ellen: "4/10/84. The office is quiet now. Just me and you. Me and you all the time now, wherever I go, whomever I'm with, whatever my actions, I hear your words and see your smile..."

The next day, April 11, she composed an open letter to family and friends: "I have some momentous news to share with you . . . Thomas has helped me focus my energies on what I believe to be the most pressing issue facing the entire world . . .I am leaving my apartment and my job . . . I am committing myself to the end of the nuclear arms race . . . I have not lost my mind. I have found my purpose."

There it is:

The straight world

the moneyed world

the world of expectations

and regrets

- excerpt from Ellen's journal

At the National Wildlife Federation, where Ellen Benjamin worked for executive vice president Jay Hair from October 1983 to April 1984, people tend toward nervous laughter when her name comes up. A spokesman for Hair says he is unavailable for comment.

"While she was with us she was a very good performer," says Ric Clay, vice president of the Federation for administration. "Then one day she simply announced that she wanted to change her life. We had heard that the reason she wanted to leave the organization was that she wanted to be a bag person. I guess you might say our reaction was disbelief.

"We parted on friendly terms. I think I told her, 'Good luck. You know, Ellen, you have your own life style, but if there's anything we can do, please let me know.'"

She offered to stay until June, but the Federation dismissed her immediately and she was able to get unemployment compensation of $206 a week. Until the money stopped coming in late November, she says she spent it on an outdoor public address system, provisions, the photocopying of leaflets and legal briefs, and paying off debts. In the meantime, her actions have left her family variously hurt, baffled and guilt-ridden.

"We were heartbroken," says an aunt, Ellen Chaffee, of Tryon, N.C. "From my viewpoint, she could be more effective with a career and using her money and her spare time for this same cause. But I respect her courage. And I respect her sticking to the cause."

"When she did it, I thought she was ready to be committed, basically," says her daughter, Katy Stone, who received her mother's castoff jewelry, clothes and car when she moved into the streets. (The wok went to a friend.) "I sort of felt like I was being abandoned. I was going to leave anyway, but I was getting pushed out before I was ready."

She says she has accepted her mother's decision. "It's her life, let her live it," Stone says from Wilmington, N.C., "If she's happy, that's the best she can hope for. I hope Thomas is keeping my mom happy. I hope he doesn't do anything to hurt her. She's been hurt enough."

Ellen's mother, Mary Stephenson, says from her home in northern Minnesota, "It's awfully hard to have your daughter just forget about her children and job and give everything away and go live in the streets. At first I was shocked and quite angry. I'm just a middle-class Middle Western mother. I really don't understand it."

"I haven't given her up," says her father, John Steel, a retired maritime artist in northern California. "Muffin is my daughter and I love her. She has always been beautiful. She has always been a good kid. I think maybe I'm to blame for this. She had a helluva good time as a kid, up until I left home and pulled a disappearing act. If you see her, tell her that I love her and that I always will. And tell her to please, please, quit it."

"We parted on friendly terms. I think I told her, 'Good luck. You know, Ellen, you have your own life style, but if there's anything we can do, please let me know.'"

She offered to stay until June, but the Federation dismissed her immediately and she was able to get unemployment compensation of $206 a week. Until the money stopped coming in late November, she says she spent it on an outdoor public address system, provisions, the photocopying of leaflets and legal briefs, and paying off debts. In the meantime, her actions have left her family variously hurt, baffled and guilt-ridden.

"We were heartbroken," says an aunt, Ellen Chaffee, of Tryon, N.C. "From my viewpoint, she could be more effective with a career and using her money and her spare time for this same cause. But I respect her courage. And I respect her sticking to the cause."

"When she did it, I thought she was ready to be committed, basically," says her daughter, Katy Stone, who received her mother's castoff jewelry, clothes and car when she moved into the streets. (The wok went to a friend.) "I sort of felt like I was being abandoned. I was going to leave anyway, but I was getting pushed out before I was ready."

She says she has accepted her mother's decision. "It's her life, let her live it," Stone says from Wilmington, N.C., "If she's happy, that's the best she can hope for. I hope Thomas is keeping my mom happy. I hope he doesn't do anything to hurt her. She's been hurt enough."

Ellen's mother, Mary Stephenson, says from her home in northern Minnesota, "It's awfully hard to have your daughter just forget about her children and job and give everything away and go live in the streets. At first I was shocked and quite angry. I'm just a middle-class Middle Western mother. I really don't understand it."

"I haven't given her up," says her father, John Steel, a retired maritime artist in northern California. "Muffin is my daughter and I love her. She has always been beautiful. She has always been a good kid. I think maybe I'm to blame for this. She had a helluva good time as a kid, up until I left home and pulled a disappearing act. If you see her, tell her that I love her and that I always will. And tell her to please, please, quit it."

Come, my friend, let us set a table in Lafayette Park, drape it with linen, heap it with silver. . .

- excerpt from Ellen's journal

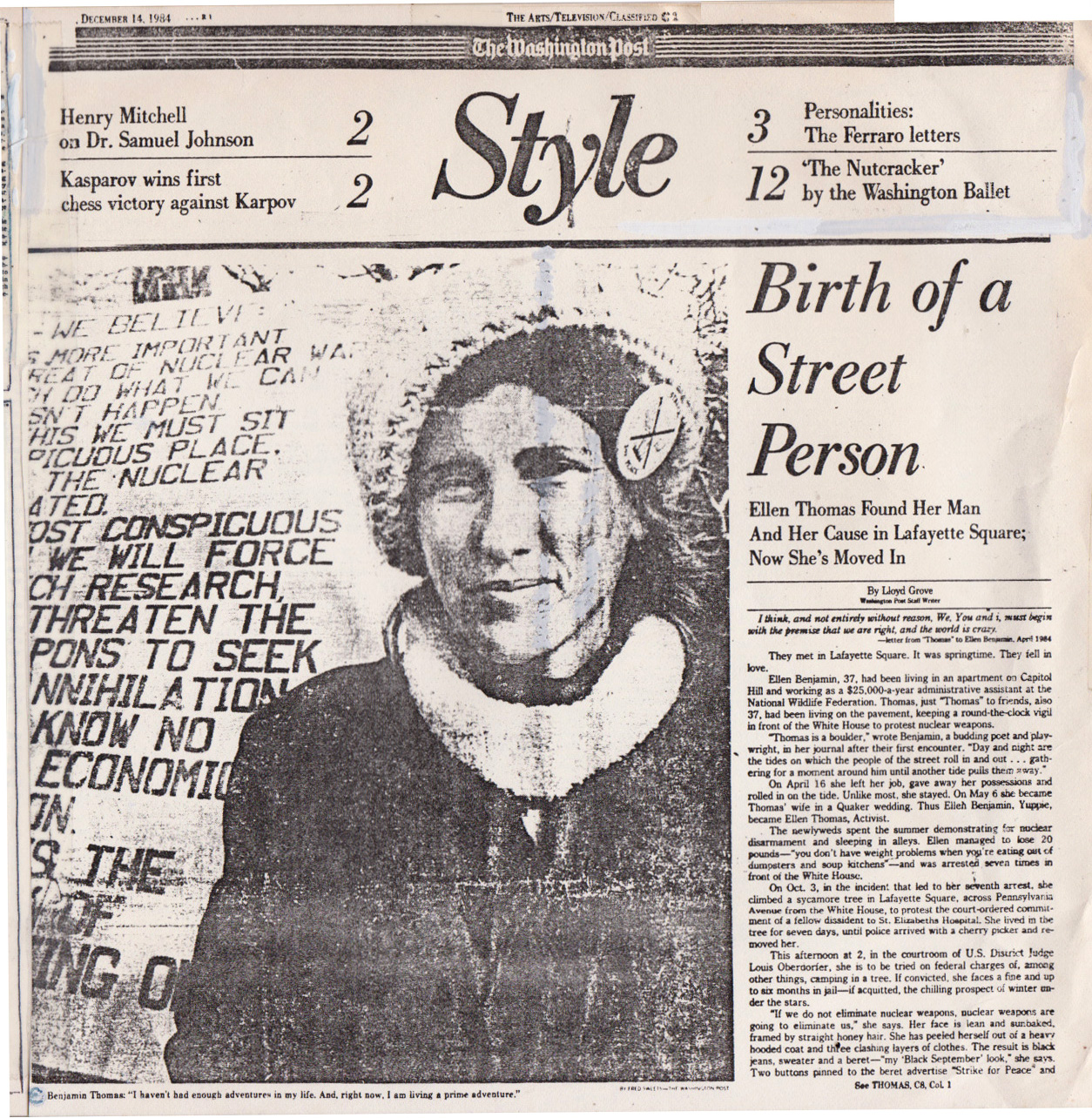

It's a bright afternoon in Lafayette Square, and the painted plywood signs ("LIVE BY THE BOMB, DIE BY THE BOMB") glimmer in the setting sun. Ellen, on a park bench, is bundled up against the chill, wearing a stringy black wig for added warmth under the beret. "I haven't eaten all day," she says. "Let's go dumpstering."

She leaps up, fairly skips across a downtown street and ducks into an alley - pausing to point out a sheltered nook where she spent the previous night - and leads her visitor to a dumpster behind Hardee's Hamburgers.

The dumpster is big and blue, smelling of soured milk. She braces her hands on the rim and climbs in. Several minutes of careful rummaging produce a plastic bag full of uneaten burgers, recently discarded and cooling in their boxes.

"The fast food places have to dump their unsold food at 11 in the morning and 4 in the afternoon," she says, tossing shreds of hamburger bun at the pigeons. "We provide for ourselves out of the waste of society. We take what we need and leave the rest for other homeless people.

"Hardee's has the best garbage," she adds.

Their wedding was an outdoor affair in Lafayette Square. The groom's mother traveled from Yonkers, N.Y., to be there. None of the bride's relatives came. The couple wore thrift-shop robes—the bride's was gray with white and gold trim, the groom's was burgundy with silver trim. It was drizzling.

Following Quaker custom, they presided at their own wedding. Various of the groom's cronies-street people, nomads, antinuclear sympathizers-spoke in support of the union. In a surge of good feeling, one of them, a panhandler by reputation, presented the couple with a machete. "I don't know why I'm doing this," he said, ceremoniously placing it on the ground. Sometime during the proceedings, it vanished.

Their wedding was an outdoor affair in Lafayette Square. The groom's mother traveled from Yonkers, N.Y., to be there. None of the bride's relatives came. The couple wore thrift-shop robes—the bride's was gray with white and gold trim, the groom's was burgundy with silver trim. It was drizzling.

Following Quaker custom, they presided at their own wedding. Various of the groom's cronies-street people, nomads, antinuclear sympathizers-spoke in support of the union. In a surge of good feeling, one of them, a panhandler by reputation, presented the couple with a machete. "I don't know why I'm doing this," he said, ceremoniously placing it on the ground. Sometime during the proceedings, it vanished.

Thomas spoke first: "Well, the reason we're here today, folks, is because Ellen thinks like me. And as long as she continues to think the way she does, then we'll be married."

Then Ellen: "Now wait a minute. That doesn't give me much room to grow."

Thomas: "All right, I'll amend that. As long as she continues to think like me, then we'll be married."

Ellen: "Wherever you go, I go."

The rain came down in earnest. "Well, I guess that's it, folks," Thomas said. "I guess you all probably want to go home now."

"And they did," says Ellen, chuckling as she recalls the occasion. "One of our friends had provided us with a banquet out of dumpsters. But nobody ate anything because they all thought Thomas wanted to get rid of everybody so he could consummate the marriage." She blushes and bursts out laughing. "It's very difficult, you know, when you live in the streets. I suppose I could write a poem about it - 'Rooftops I Have Known.' "

Thomas spoke first: "Well, the reason we're here today, folks, is because Ellen thinks like me. And as long as she continues to think the way she does, then we'll be married."

Then Ellen: "Now wait a minute. That doesn't give me much room to grow."

Thomas: "All right, I'll amend that. As long as she continues to think like me, then we'll be married."

Ellen: "Wherever you go, I go."

The rain came down in earnest. "Well, I guess that's it, folks," Thomas said. "I guess you all probably want to go home now."

"And they did," says Ellen, chuckling as she recalls the occasion. "One of our friends had provided us with a banquet out of dumpsters. But nobody ate anything because they all thought Thomas wanted to get rid of everybody so he could consummate the marriage." She blushes and bursts out laughing. "It's very difficult, you know, when you live in the streets. I suppose I could write a poem about it - 'Rooftops I Have Known.' "

We are surrounded by insanity, Thomas and I. Sometimes I wonder how he managed to stay so blessedly sane during these three years of waiting.

-excerpt from Ellen's journal

Thomas has been a fixture in front of the White House for the last 31/2 years, fasting, befriending street people, preaching to passersby, skirmishing with the U.S. Park Police and grappling with the elements. He is short and scrappy, built for survival. His wildly forked beard and piercing gaze, over glasses that sit pedantically on the tip of his nose, give him the look of a Dostoevsky hero.

"When I met Ellen, I figured that she was just another one of the thousands of people who pass by, who show some passing interest and then go back to their lives. It didn't work out that way," he says, sipping steaming coffee out of a plastic cup. "I guess it wasn't love at first sight, but it was pretty quick . . . I realized that it was extremely extreme."

He was born William Thomas Hallenback, Jr. in Tarrytown, N.Y., but pared down his name, as he did his life, to the barest essentials. An erstwhile truck driver and jewelry maker, he describes himself as a former heroin addict who served eight years in prison for offenses ranging from car theft in New York to visa violations in the Middle East and Great Britain.

He says he attempted several times to walk across the Sinai Desert from Egypt to Israel in the cause of world peace, an effort that earned him eight months in an Egyptian prison in 1978. In London, he tried to renounce his American citizenship by tossing his passport into the Thames. British authorities eventually deported him to the United States, putting him on a plane to New York in the company of two policemen in 1980.

He says he naturally gravitated to Washington in 1981, spending several months with Mitch Snyder's Community for Creative Non-Violence before launching his antinuclear vigil in June of that year. Since then he has been arrested 16 times by the Park Police on charges ranging from illegal camping to disorderly conduct. Three years ago on Christmas Day, he tried to dramatize his cause by knotting a rope around his wrists, scaling a lamppost on Pennsylvania Avenue and dangling from it in an attitude of martyrdom until the fire department cut him down.

Thomas acknowledges that "a lot of people probably think I'm crazy, and I'm constantly questioning my sanity." But among those who defend his position are Mitch Snyder - "There's a basic simplicity and truth to what he's doing" -- and Canadian journalist William Johnson, Washington bureau chief of the Toronto Globe.

"He is in a long tradition in Christendom that goes back all the way to St. Benedict," says Johnson, an ex-Jesuit seminarian who lets Thomas and Ellen use his apartment to take showers. "It's a tradition of withdrawing from the world, of 'renouncing the pomps.' Thomas has proven the seriousness of his commitment by enduring for a very long time."

"I admire the man so much, I think he's a Socrates or a Gandhi," says Ellen. "All I really ever wanted to do was to sit at his feet."

Thomas has been a fixture in front of the White House for the last 31/2 years, fasting, befriending street people, preaching to passersby, skirmishing with the U.S. Park Police and grappling with the elements. He is short and scrappy, built for survival. His wildly forked beard and piercing gaze, over glasses that sit pedantically on the tip of his nose, give him the look of a Dostoevsky hero.

"When I met Ellen, I figured that she was just another one of the thousands of people who pass by, who show some passing interest and then go back to their lives. It didn't work out that way," he says, sipping steaming coffee out of a plastic cup. "I guess it wasn't love at first sight, but it was pretty quick . . . I realized that it was extremely extreme."

He was born William Thomas Hallenback, Jr. in Tarrytown, N.Y., but pared down his name, as he did his life, to the barest essentials. An erstwhile truck driver and jewelry maker, he describes himself as a former heroin addict who served eight years in prison for offenses ranging from car theft in New York to visa violations in the Middle East and Great Britain.

He says he attempted several times to walk across the Sinai Desert from Egypt to Israel in the cause of world peace, an effort that earned him eight months in an Egyptian prison in 1978. In London, he tried to renounce his American citizenship by tossing his passport into the Thames. British authorities eventually deported him to the United States, putting him on a plane to New York in the company of two policemen in 1980.

He says he naturally gravitated to Washington in 1981, spending several months with Mitch Snyder's Community for Creative Non-Violence before launching his antinuclear vigil in June of that year. Since then he has been arrested 16 times by the Park Police on charges ranging from illegal camping to disorderly conduct. Three years ago on Christmas Day, he tried to dramatize his cause by knotting a rope around his wrists, scaling a lamppost on Pennsylvania Avenue and dangling from it in an attitude of martyrdom until the fire department cut him down.

Thomas acknowledges that "a lot of people probably think I'm crazy, and I'm constantly questioning my sanity." But among those who defend his position are Mitch Snyder - "There's a basic simplicity and truth to what he's doing" -- and Canadian journalist William Johnson, Washington bureau chief of the Toronto Globe.

"He is in a long tradition in Christendom that goes back all the way to St. Benedict," says Johnson, an ex-Jesuit seminarian who lets Thomas and Ellen use his apartment to take showers. "It's a tradition of withdrawing from the world, of 'renouncing the pomps.' Thomas has proven the seriousness of his commitment by enduring for a very long time."

"I admire the man so much, I think he's a Socrates or a Gandhi," says Ellen. "All I really ever wanted to do was to sit at his feet."

I observed Mrs. Thomas climb out of what appeared to be a blue hammock 15 feet into the tree and attempt to climb to the highest point. Ofc. Chesley and I climbed directly behind her. She stopped climbing approx 30 feet off the ground and I was able to hold her by the collar of her snowmobile suit to prevent her from climbing any further, or falling. Mrs. Thomas advised me that removing her from the tree would do no good because upon her release she would only climb it again, she was making a political statement.

- from Oct. 10,1984, arrest report of U.S. Park Police Officer F.R. Howard

Ellen's tree trial today is a drop in a maelstrom of litigation involving all kinds of protesters — Ellen and Thomas among them — the Interior Department and scores of government prosecutors and court-appointed defense lawyers. The cases pit the government's concerns for White House security against the protesters' claims under the First Amendment.

Ellen says she spent a week living in a tree last October to call attention to the plight of Casimer Urban, Jr., who was arrested last July on suspicion of breaking the no-camping rule. He'd reclined and closed his eyes beside a sign that said, "Welcome to Reaganville 1984, where sleep is considered a crime."

He was ordered to St. Elizabeths for psychiatric evaluation, and after being held there for 31/2 months, during which he had to take powerful medications under a court order, he was pronounced competent to stand trial. He spent an additional three weeks in jail before the trial judge dismissed the case for lack of evidence.

"The government did to Cass exactly what they do to dissidents in the Soviet Union," Ellen says.

This week she and Thomas have been in court a great deal. Yesterday, while Ellen prepared for her tree trial, Thomas divided his time between a motions hearing in D.C. Superior Court, where a misdemeanor case against him was dismissed, and an argument in federal appeals court to overturn several of his camping convictions.

On Monday, Superior Court Judge Steffen Graae sentenced him to three years' probation and 250 hours of community service on a felony conviction arising from a 1982 incident in which he set fire to a sign of a mushroom cloud ("Revelation—this need not be our end") and inadvertently damaged a pillar in front of the Old Executive Office Building.

Thomas has also filed a civil suit, with Ronald Reagan leading a cast of defendants and "unindicted pawns," demanding that he be permitted "to maintain a continuous nonviolent reproachful presence on the White House sidewalk."

"We're not trying to prohibit demonstrating in front of the White House," says Royce Lamberth, chief of the civil division of the U.S. Attorney's Office, which has been served with Thomas' suit. "But they're not legitimate demonstrators if they don't conform to the rules for demonstrating. Why do they have to violate the regulations? Why can't they conform? That's the part I don't understand."

Living in the public eye as we do, we experience human behavior at its most honest — and therefore, while it seems to be more insane than the "straight" world, the park is really a halfway house from the desolation of living lies to the joy of living truth.

- excerpt from Ellen’s journal

With occasional respites in friends’ apartments, Ellen has been in the street for seven months.

Her body, once soft, is now "as hard and lean as a 20-year-old girl’s," she says. She has revised her play, "The Grate People," into a soap opera, "As the World Burns." She has gained the trust of other street people—"a bunch of free spirits, the last of the frontiersmen," she says. Mark Parker, 21-year-old wanderer from Texas, says, "With Ellen, we once thought we had a cop on our hands."

And she has contended with Concepcion Picciotto, a small woman who wears a metal helmet under an ever-present black wig, all of it held in place by a scarf. For Picciotto, who has faithfully stood vigil alongside Thomas since 1981, Ellen’s arrival was an invasion.

"You are a vicious woman," she spits at Ellen. "There has been no peace since you arrived on the sidewalk ... You just come in, you don't know nothing. You don't endure nothing.

"I endure you, Concepcion, I endure you." [For the sake of history, Ellen is offended by this passage.]

Indeed, she has explored new vistas of endurance.

"There are rats in the alleys, lots of rats,"

Ellen says. "That gave me a little queasy feeling at first, particularly sleeping with them, but rats are God's creatures. They're just squirrels with skinny tails basically. I have a lot of respect for rats. They have the ability to survive despite all the handicaps that society tries to place on them."

The evidence suggests that Ellen does, too.

"I work harder now than I've ever worked in my life. We have a job to be done and it's a job that is vital to the survival of the human race." She grins. "I'm not saying I like it. If I had my 'druthers,' I'd 'druther' live on a tropical island someplace, and just spend my time writing poems - and climbing coconut trees."

"There are rats in the alleys, lots of rats,"

Ellen says. "That gave me a little queasy feeling at first, particularly sleeping with them, but rats are God's creatures. They're just squirrels with skinny tails basically. I have a lot of respect for rats. They have the ability to survive despite all the handicaps that society tries to place on them."

The evidence suggests that Ellen does, too.

"I work harder now than I've ever worked in my life. We have a job to be done and it's a job that is vital to the survival of the human race." She grins. "I'm not saying I like it. If I had my 'druthers,' I'd 'druther' live on a tropical island someplace, and just spend my time writing poems - and climbing coconut trees."

Conviction |

Legal Overview | Regulations | Ellen Biography