To that end, he embarked on an odyssey six years ago,

leaving behind a wife and a New Mexico jewelry business, to

experience life and find out what is true and what is not.

At the time, he was studying the Bible, and he found himself

preoccupied with the notion that money is the root of all evil."I had a house, three cars, bank accounts, insurance policies and I thought: I have all these things, these 'rewards',and yet the Bible tells me I am not living the right way...And I thought, if

that was true - if money led to evil, and if you need money to live - then the syllogism followed that evil is necessary, which was not palatable to me."

So he set out to see if he could live without money or jobs,

in order to prove that money was unnecessary. "To tell the

truth," he says, I had some anxieties. I was leaving my wife

behind. I said, "Is this rational? Are you sane? But I had to

test this out. And I knew that if I found it to be true, then the

world was living a radically irrational existence."

Thomas' journey took him to New York where he worked for a

week as a carpenter to make enough money for a one way ticket to

Casablanca. From there he walked on foot to Cairo. He had no

money.

"There were days I went without food," he says, and in six

months I did sleep outside for about six weeks. But otherwise

food and shelter were just provided. I never asked anybody for

anything. I had a blanket over my shoulder and the clothes I was

wearing: that was all. People would just come up to me and say,

"Where are you going? That's a long way. Where are you sleeping?

Come with me." They asked me, they frequently asked me what I

needed. I never asked."

He returned to the United States for a time, working as a

dispatcher for a cab company and as a stone carver. Then he

resumed his journey. Over several years, he said, he traveled

back and forth across Europe. HE found himself last year in

London, where he was jailed for several months after overstaying

his visa. Eventually the authorities deported him to the United

States. He arrived last October at Kennedy National Airport,

where he had to be forcibly removed from the plane. "I was

dragged into the customs office," he says, "where I was told I

was now in America and free to go where I pleased."

The seed to that ordeal was a decision he had made in London

months before: He no longer wished to be an American citizen. In

the course of his wanderings, he had come the conclusion that the

United States was contributing to the destruction of the earth

and exploiting its inhabitants. Therefore, for him to advise

others not to fight over land and exploit one another, while he

was benefiting from the American passport, seemed hypocritical to

him. Association with a country whose ideals he loved but while

practices he abhorred was inconsistent with his goal of attaining

moral perfection.

So he had taken the waterproof wallet containing his union

cards, his social security card, and his passport and had thrown

it into a lake in Hyde Park, England. "I assumed," he says, that

there was nothing wrong with throwing away my passport because I

knew myself to be a free man... Then I decided I would walk back

to the Mideast, but when I got to Dover, I was arrested...

"I argued that I couldn't have a visa, because I didn't have

a passport, for reasons I have already explained. Additionally,

visas are designed to control populations, and since I was

leaving the country, I was no threat to the population...They had

no right to tell me I had to be an American. It is not for anyone

else to decide who I am; it is for me to decide..."

Thomas has written down his thoughts and his experiences, an

account that exceeds 300 pages. In March, he telephoned the

Soviet Embassy here, saying he had a manuscript dealing with the

conflict between America's ideals and its practices and asking if

the Soviet embassy was interested. He says he has no sympathy for

communism, but thought he'd try to communicate his ideas on this

through another channel. When he arrived at the embassy, he met

with V. Doroshenko, the third secretary in the information

department.

According to Thomas, he and Doroshenko exchanged ideas, and

Doroshenko asked if there was anything the embassy could do for

Thomas, who told Doroshenko he was interested in peace. Thomas

said Doroshenko then told him that the Russians too, were

interested in peace. "And then I told him," Thomas recalled,

"that I thought this mutual buildup of nuclear weapons had to do

with mutual fear between the two nations. And he said yes, he

thought that was true. And then I told him that in order to prove

that Americans had nothing to ___ of the Russians, I wanted to

surrender myself to the Soviet Union. He said, "You don't have to

do that," and I said that nevertheless I would. He said, "You

cannot, and I said, "I will. I am not leaving. So they had me

removed by the police."

Doroshenko confirmed that the meeting took place and

confessed to having been puzzled by Thomas' calm refusal to

abandon the idea of surrender. "I told him," said Doroshenko,

that he would have to go to the chancery first if he wanted to go

to the Soviet Union, but he wouldn't move, so what could I do?

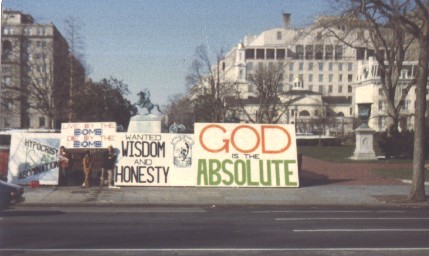

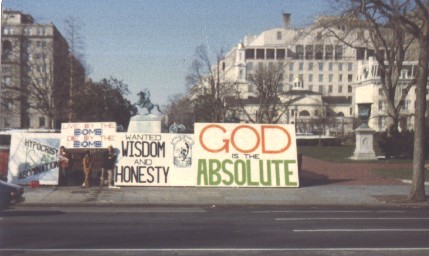

The young scriptwriter with the curly hair who had stopped

hours before to ask Thomas what he stood for had been preceded by

an old man with no hair who was carrying a lot of newspapers

under his arms. "What is this about?" he asked. The papers

flapped under his arms like wings. Thomas answered: "Wisdom and

peace." The old man's mouth fell open. Then he walked away,

shaking his head vigorously, and saying, "You never let up do

you?"

Thomas thanked him

Concepcion Information List | Conchita Personal Story

Photographs | The President's Neighbor