The Marijuana "High"

Table 3.1 Psychoactive Doses of THC in Humans

| THC Delivery System | THC Dose Administered | Resulting Level of THC in Plasma | Subjects' Reactions | Reference |

| One 2.75% THC cigarette smoked | 0.32 mg/kg* | 50-100 ng/ml | At higher level subjects felt 100% "high" and psychomotor performance is decreased. At 50 ng/ml subjects felt about 50% "high" | Heishman and coworkers 1990 |

| 1 gm marijuana cigarette smoked (2% or 3.5% THC) | 0.25-0.50 mg/kg* | Not measured | Enough to feel psychological effects of THC | Kelly and coworkers 1993 |

| 19 mg THC cigarette smoked (approx 1.9% THC) | Approx. 0.22 mg/kg** | 100 ng/ml | Subjects felt "high" | Ohlsson and coworkers 1980 |

| 5 mg THC injected i.v. | Approx. 0.06 mg/kg** | 100 ng/ml | Subjects felt "high" | |

| Chocolate chip cookie containing 20 mg THC | Approx. 0.24 mg/kg | 8 ng/ml | Subjects rated "high" as only about 40% | |

| 19 mg THC cigarette smoked to "desired high" | 12 mg was smoked (7 mg remained in cigarette butt) | 85 ng/ml (after 3 min.) 35 ng/ml (after 15 min.) | Subjects felt "high" after 3 minutes, and maximally high after 10-20 minutes (average self ratings of 5.5 on a 10-point scale) | Lindgren and coworkers 1981 |

| 5 mg THC injected i.v. | 0.06 mg/kg*** | 300 ng/ml (after 3 min.) 65 ng/ml (after 15 min.) | Subjects felt maximally "high" after 10 minutes (average self ratings of 7.5 on a 10-point scale) |

* Subjects' weights and cigarette weights were not given. Calculation based on 85 kg body weight, and 1g cigarette weight. Note that some THC would have remained in the cigarette butt and some would have been lost in side-stream smoke, so these represent maximal possible doses administered. Actual doses would have been slightly less.

** Based on estimated average weight of 85 kg for 11 men aged 18-35 years.

*** Based on approximately weight of 80 kg (subjects included men and women).

Addiction. Substance dependence.

Craving refers to the intense desire for a drug and is the most difficult aspect of addiction to overcome.

Physiological dependence is diagnosed when there is evidence of either tolerance or withdrawal; it is sometimes, but not always, manifested in substance dependence

Reinforcement. A drug - or any other stimulus -- is referred to as a reinforcer if exposure to it is followed by an increase in frequency of drug-seeking behavior. The taste of chocolate is a reinforcer for biting into a chocolate bar. Likewise, for many people, the sensation experienced after drinking alcohol or smoking marijuana is a reinforcer.

Substance dependence is a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological symptoms indicating that a person continues use of the substance despite significant substance-related problems.

Tolerance is the most common response to repetitive use of a drug and can be defined as the reduction in responses to the drug after repeated administrations.

Withdrawal. The collective symptoms that occur when the drug is abruptly withdrawn are known as withdrawal syndrome and are often the only evidence of physical dependence.

(1) Tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

(a) A need for markedly increased amount of the substance to achieve intoxication or desired effect.(b) Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance.

(2) Withdrawal, as defined by either of the following:

(a) The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance to achieve intoxication or desired effect.(b) The same (or closely related) substance is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms.

(3) The substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended.

(4) There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use.

(5) A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance

(e.g. visiting multiple doctors driving long distances), use the substance

(e.g., chain-smoking), or recover from its effects.(6) Important social occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use

(7) The substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem or exacerbated by the substance

(e.g., current cocaine use despite recognition of cocaine-induced depression or continued drinking despite recognition that an ulcer was made worse by alcohol consumption).

Substance abuse with physiological dependence is diagnosed if there is evidence of tolerance or withdrawal.

Substance abuse without physiological dependence is diagnosed if there is no evidence of tolerance or withdrawal.

Reinforcement

Tolerance

respiratory depressant effects, so heroin users tend to increase their daily doses to reach their desired level of euphoria, thereby putting them at risk for respiratory arrest. Because tolerance to the various effects of cannabinoids might develop at different rates, it is important to evaluate independently their effects on mood, motor performance, memory, and attention, as well as any therapeutic use under investigation.

Withdrawal

A distinctive marijuana and THC withdrawal syndrome has been identified, but it is mild and subtle compared to the profound physical syndrome of alcohol or heroin withdrawal 31 73 The marijuana withdrawal syndrome includes restlessness, irritability, mild agitation, insomnia, sleep EEG disturbance, nausea, and cramping

(table 3.2). This syndrome, however, has only been reported in a group of adolescents in treatment for substance abuse problems or in a research setting where subjects were given marijuana or THC on a daily basis 73

Table 3.2 Drug Withdrawal Symptoms

| Nicotine | Alcohol | Marijuana | Cocaine | Opioids (e.g. heroin) |

| Restlessness Irritability Dysphoria Impatience, hostility Depression Difficulty concentrating Anxiety Decreased heart rate Increased appetite or weight gain |

Tremor Irritability Nausea Sleep disturbance Tachycardia Perceptual distortion Hypertension Sweating Seizures Alcohol craving Delirium tremens (severe agitation, confusion, visual hallucinations, fever, profuse sweating, nausea, diarrhea, dilated pupils) |

Restlessness Irritability Mild agitation Sleep EEG disturbance Insomnia Nausea, Cramping |

Dysphoria Depression Bradycardia Sleepiness, fatigue Cocaine craving |

Restlessness Irritability Increased sensitivity to pain Dysphoria Insomnia, anxiety Muscle aches Nausea, cramps Opioid craving |

Table legend. This summary of withdrawal symptoms is from O'Brien's 1996 review. 112 In addition to the established symptoms listed above, two recent studies have reported several more. A group of adolescents under treatment for conduct disorders also reported fatigue and illusions or hallucinations after marijuana abstinence (this study is discussed further under the section on "Prevalence and Predictors of Dependence"). 31 In a residential study of daily marijuana users, withdrawal symptoms included sweating and rhinorrhea (runny nose), in addition to those listed above (this study is discussed further under the section on "Tolerance"). 31

Craving

another drug's effects. Some of these addiction medication drugs also block craving. For example, methadone blocks the euphoria effects of heroin and also reduces craving.

Marijuana Use and Dependence

Prevalence of Use

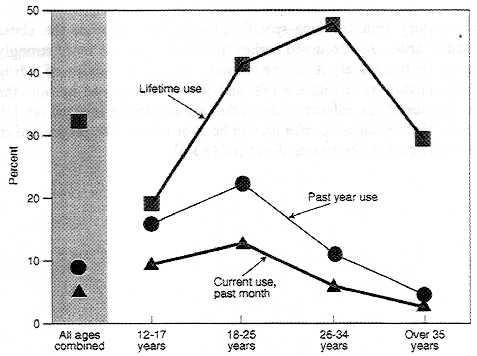

Figure 3.1 Age distribution of marijuana users among the general population

Prevalence and Predictors of Drug Dependence

Table 3.3 Factors that are correlated with drug dependence

- Pharmacological effects of the drug

- Gender

- Age

- Genetic factors

- Individual risk-taking propensities

- History of prior drug use

- Availability of the drug

- Acceptance of the use of that drug within society

- Balance of social reinforcements and punishments for use

- Balance of social reinforcements and punishments for abstinence

Source: Crowley and Rhine (1985)32

Table legend. Factors that can influence the likelihood that an individual will become dependent on a drug.

Table 3.4 Prevalence of Drug Use and Dependence Among the General Population

| Drug Category | Proportion Who have Ever Used Different Types of Drugs | Proportion Of Users That Ever Became Dependent |

| Tobacco | 76 % | 32 % |

| Alcohol | 92 % | 15 % |

| Marijuana (including hashish) | 46 % | 9 % |

| Anxiolytics (including sedatives and hypnotic drugs) |

13 % | 9 % |

| Cocaine | 16 % | 17 % |

| Heroin | 2 % | 23 % |

Table legend. The table shows estimates for the proportion of people among the general population who used or became dependent on different types of drugs. The proportion of users that ever became dependent includes anyone who was ever dependent - whether it was for a period of weeks or years - and thus includes more than those who are currently dependent. The diagnosis of drug dependence used in this study was based on DSM-III-R criteria. 2 Adapted from table 2 in Anthony and coworkers (1994). 8

Table 3.5 Psychiatric disorders associated with drug use among children

| Relative prevalence of diagnoses for psychiatric disorders associated with drug use among children | ||

| . | ||

| Drug Use | Boys | Girls |

| Weekly alcohol use | 6.1 | 1.6 (n.s.) |

| Daily cigarette smoking | 9.8 | 2.1 (n.s.) |

| Any illicit substance use | 3.2 | 5.3 |

Table legend. The subjects ranged in age from 9-18 years, with an average age of 13 years.

A ratio of one means that the relative prevalence of the disorder is equal among those who do and those who do not use the particular type of drug, that is, there is no measurable association. A ratio greater than one indicates that the factor is associated. Thus boys who smoke daily are as almost ten times more often diagnosed as having a psychiatric disorder (not including substance abuse) as those who smoke less. Substance abuse was excluded from this analysis since the subjects being analyzed were already grouped by their high drug use. Except where noted (n.s.) all values are statistically significant..

Data are from table 4 in Kandel and coworkers 1997 78

Marijuana Dependence

The Link Between Medical Use and Drug Abuse

Medical Use and Abuse of Opiates

There is no evidence to suggest that the use of opiates or cocaine for medical purposes has increased the perception that the illicit use of these drugs is safe or acceptable. Clearly, there are risks that patients may abuse marijuana for its psychoactive effects as well as risks of diversion of marijuana from legitimate medical channels into the illicit market. Again, this does not differentiate marijuana from many accepted medications that are abused by some patients or diverted from medical channels for non-medical use. Where this has taken place, medications have been placed in Schedule II of the Controlled Substances Act, which brings the drug under stricter control, including quotas on the amount that can be legally manufactured (see chapter 5 for discussion of the Controlled Substances Act). This scheduling also signals to physicians that the drug has abuse potential and that they should monitor the use of the medication by patients that may be at risk for drug abuse.

Effect of Marijuana Decriminalization

Monitoring the Future, the annual survey of values and life-styles of high school seniors, revealed that high school seniors in decriminalized states reported using no more marijuana than did their counterparts in states where marijuana was not decriminalized. 71 Another study reported somewhat conflicting evidence indicating that decriminalization had increased marijuana use. 104 That study used data from the Drug Awareness Warning Network (DAWN), which has collected data since 1975 on drug-related emergency (ER) room cases. Among states that had decriminalized marijuana in 1975-1976, there was a greater increase from 1975 to 1978 in the proportion of ER patients who had used marijuana than in states that did not decriminalize marijuana (table 3.6). Despite the greater increase among decriminalized states, by 1978, the proportion of marijuana users among ER patients was about equal in states that did and states that did not decriminalize marijuana. This is because the non-decriminalized states had higher rates of marijuana use before decriminalization. In contrast to marijuana use, rates of other illicit drug use among ER patients were substantially higher among states that did not decriminalize

marijuana use. Thus, there are different possible reasons for the relatively greater increase in marijuana use in the decriminalized states. On the one hand, decriminalization might have led to an increased use of marijuana (at least among people who seek health care in hospital emergency rooms). On the other hand, the lack of decriminalization might have encouraged greater use of drugs that are even more dangerous than marijuana. Interpretations are ambiguous.

Table 3.6 Decriminalization and Marijuana Use

| Effect of Decriminalization on Marijuana Use in ER Cases | |||

| . | Total Reports of Drug Use per ER | ||

| . | Time Period (States the decriminalized so after 1975 and before 1978 | States that decriminalize marijuana. | States that did not Decriminalized marijuana |

| Marijuana use | 1975 | 0.8 | 1.5 |

| 1978 | 2.7 | 2.5 | |

| Other drug use | 1975 | 47 | 55 |

| 1978 | 55 | 70 | |

Table legend. The values shown indicate the frequency of drug use among ER patients in states that decriminalized marijuana from July 1975- July 1977 and in those that did not. Data are based on patient self-reports. The 1975 values reflect ER marijuana reports before or in the first months of decriminalization, whereas the 1978 values reflect ER reports when decriminalization laws had been in effect at least one year. The 1978 levels are median values for quarters in 1978, and are derived from figures 1 and 2 in Model (1993). 104 The values in the column for states that did not decriminalize represent what might have been seen if the states in the first column had not decriminalized.

Effect of the Medical Marijuana Debate

Psychological Harms

a Although Arizona also passed a medical marijuana referendum, it was embedded in a broader referendum concerning prison sentencing. Hence the debate in Arizona did not focus on medical marijuana the way it did m California, and changes in Arizona youth attitudes likely reflect factors peripheral to medical marijuana.)

Psychiatric disorders

Schizophrenia

schizophrenia are likely to be at greater risk of suffering adverse psychiatric effects from the use of cannabinoids.

Cognition

Psychomotor Performance

performance on flight simulator tests was impaired (Yesavage and coworkers 1985 162). Before the tests, however, they told the study investigators that they were sure their performance would be unaffected.

Chapter 3 Continued ----->>>>