By Monte Reel He's locked into a Zen-like stillness, allowing snowflakes to frost his untamed beard as he contemplates the chain-like nature of existence: Fall begets winter, which begets the chill that sinks into his bones, which begets an impulse to sip hot coffee, which begets a swelling of the bladder, which begets an uncomfortable dilemma that regularly vexes Donn Congdon* during these bitter days and nights. "The killer is that you have to stay within three feet of the signs at all times or the police can legally take them away," he says. Congdon helps maintain one of two anti-nuclear weapons vigils across from the White House on the sidewalk fronting Lafayette Square. With a partner who handles the night shift, they establish a constant presence, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. So does Concepcion Picciotto, who has stayed day and night for two decades. Other demonstrations come and go, but the residents of 1601 Pennsylvania Ave. don't. They are the die-hards. Normally Congdon can go four or five hours without a bathroom break, which corresponds to the routine of a friend who stops by each afternoon to spell him during a short break. But the wicked chain of cause-and-effect that accompanies the annual shift into winter threatens the balance. "I try to think warm thoughts," he says, waiting, chilling. "Peace in the world would be cool. Or warm." The vigil keepers admit to frequent discomfort, but they won't fish for sympathy. They know that no one is forcing them to be there. And they feel certain that a lot of people, especially the U.S. Park Police, would prefer they leave. The keepers list some of the regulations that work against them as evidence. They can't fully recline because that would violate laws prohibiting camping. They can't take shelter under anything that could be construed as a structure, be it temporary or permanent. They can't abandon their signs. And, according to a policy that has been exhaustively tested, they can't deploy squirrels on tactical missions. The squirrels that freely scamper across Congdon as he sits under a tarp illustrate a few truths about life at 1601 Pennsylvania Ave. First: It can get very lonely. When the weather turns nasty, squirrels are often the only company. The buckets of nuts that Congdon and the others keep on hand have broken down the barriers that traditionally divide man and rodent: All fear is gone. A few years ago, the keepers tried to use this to their advantage, demonstrating a second truth: An abundance of time to sit and think breeds creativity. It was an ambitious plan that the vigil keepers, in retrospect, admit was a long shot. It began with a shelled peanut, a piece of shoestring, and a balloon. The balloon was tied to the string, the string was tied to the peanut. A slogan was written on the balloon: "Nuts Not Nukes." They repeated this until their bag of balloons was empty. As if knowing what was expected of them, the squirrels took peanuts in mouth and went to work. They ran with valiant abandon, balloons floating proudly behind as they zigzagged out of Lafayette Square. Some scrabbled up trees, some haltingly scurried down the street. Many of the balloons popped. But the keepers watched a few brave squirrels bound through the gated fence and onto the White House lawn, balloons intact. Like proud elders cheering on their proteges, they watched the squirrels dash and weave as the White House guards -- "lawn ninjas" in vigil lexicon -- began the chase. "We're now under the threat that if they see another squirrel with a balloon, we go to jail," says Rudy, Congdon's night-shift partner. "They're considered threats to national security." The keepers have not used the squirrels since. A Park Police spokesman wouldn't comment on the specific incident, but Congdon and Rudy, who wouldn't give his last name, have pictures of the police shutting the ballooning operation down. So these days, despite their proven potential to make a more effective and flashy statement, the squirrels lead lives sapped of the adrenal excitement they once tasted. The keepers say they can relate. In the early hours of morning, the 1600 block of Pennsylvania Avenue is one of the busiest streets in Washington. Though it is officially closed to traffic, a steady rumble of vehicular activity confronts the two vigil keepers who try to get some sleep. Snowplows make repeated passes, as do marked and unmarked security vehicles. The street lights are unrelenting. It's 1 a.m. on Friday, and Picciotto is cocooned in translucent plastic. Peel back the plastic, the blankets, the parka, the scarves, and there she is: sitting on a wooden plank, upright, ever mindful of the camping statute. Picciotto is the dean of the keepers, a Helen Thomas-like figure who has been keeping an eye on the White House since the Carter administration. Within her plasticized shelter -- don't call it a tent, because that would constitute a "structure" -- she keeps a copy of a photograph of herself as a young woman in Madrid. She is standing gowned in what looks to be some sort of a drawing room. The photo is offered as a counterpoint to the 57-year-old woman she has become. Her complexion is weathered, its ruddier elements surfacing in the capillaries that spider across her cheeks. "Without sacrifice," she says, "you can't achieve anything." She didn't start out as a nuclear protester. She originally came to 1601 to take her battle for custody of her daughter straight to the top. Soon she met William Thomas, the man who started the first permanent anti-nuclear vigil here. Thomas, who eventually founded the peace group called the Proposition One Committee, befriended her. A few yards from her plasticized lair, a pair of eyes stare out from beneath Rudy's plastic encampment. He's not accustomed to much foot traffic passing by, and he's eager to talk. "Since 9/11, man, it's hard not to feel like the Maytag repairman out here," says Rudy. Occasionally he'll spot the president or the first lady across the street, and they'll wave. The Clintons never did, he says. He figures that might have been a result of the sign that read "WAR CRIMINAL" and showed Bill Clinton's face. "He's a human being, you know," Rudy says of Bush. "I wouldn't want his job. He's got some hard shots to call. But he's the guy there, so he gets the heat." Sitting and sleeping during the hours when the only people who see them are the security guards might not seem particularly effective protest, but Rudy says it's vital. He concedes he might not have lived up to his potential, but says the vigil satisfies his desire to contribute to a free society. "That we're willing to do this 24/7 constitutes a sense of urgency," says Rudy, 53. Then he acknowledges, "It also illustrates the futility of individual effort." Awaiting a decisive triumph of peace over violence, he has taken solace in minor victories. During a sleet storm, police told him the umbrella under his tarp rendered it a structure. When he removed the umbrella, he says, the ice that had formed on the plastic retained the umbrella's shape overhead. "It didn't even move," he says, relishing the memory. Congdon has stood and sat at 1601 off and on since 1981. He hasn't missed a day since 1999. He calls it his "Cal Ripken streak." The most unbearable winter weather he can remember was the beard-icer that accompanied President Ronald Reagan's second inauguration, in January 1985. Like his compatriots, he has a few secrets to beat the cold. "We're not allowed space heaters," he says. "But sometimes I light a candle." Picciotto says she sometimes has to get someone to spell her while she changes into dry, warm clothes. Rudy confesses to sometimes, but not always, smuggling in a sleeping bag. For several weeks, the keepers have had company from the Women's Peace Vigil -- a group of women wearing pink and opposing war. Some tried to stay overnight, but they say the police told them they couldn't: That right was reserved for the vigils manned by Picciotto and Congdon and Rudy. The longtime keepers like having the company, even if it's not round-the-clock. But it's clear from listening that true street credibility comes only when time is measured in years. "It's probably good they aren't out here at night," Rudy says of the group. "They were fasting, so that probably wouldn't have been a good idea. I'd never give up food and do this." This week, many pathways in Lafayette Square were snow-covered. But not the stretch of pavement near the keepers. As Congdon relieved Rudy after the snowfall on Thursday morning, he found him shoveling around his post. Throughout that day several people would ask Congdon if he was doing all right. "Not too cold, are you?" a passerby asked. "I've seen worse," Congdon replied. "Do you need anything?" "I'm fine," he said. "It's pretty easy for me. I've got this nice, thick beard. I'll drink a lot of coffee."

* [Note: Donn's last name is Condron, not Congdon]

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, December 8, 2002; Page C01

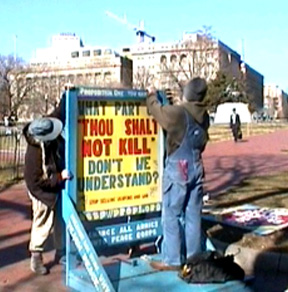

camera, wishes members of the

Nipponzan Myooji Buddhist

Order well as they leave

their vigil at day's end.

(Photos Lucian Perkins --

The Washington Post)

Squirrels for Peace

The Night Shift

Battling Winter